At a time when India is celebrating Saikhom Mirabai Chanu’s silver in weightlifting at the Tokyo Olympics, and Priya Malik’s gold at the World Cadet Wrestling Championships in Budapest, 13 women athletes from across South Asia came together on Sunday for an online discussion titled ‘Women in Sport: Challenges and Wins’.

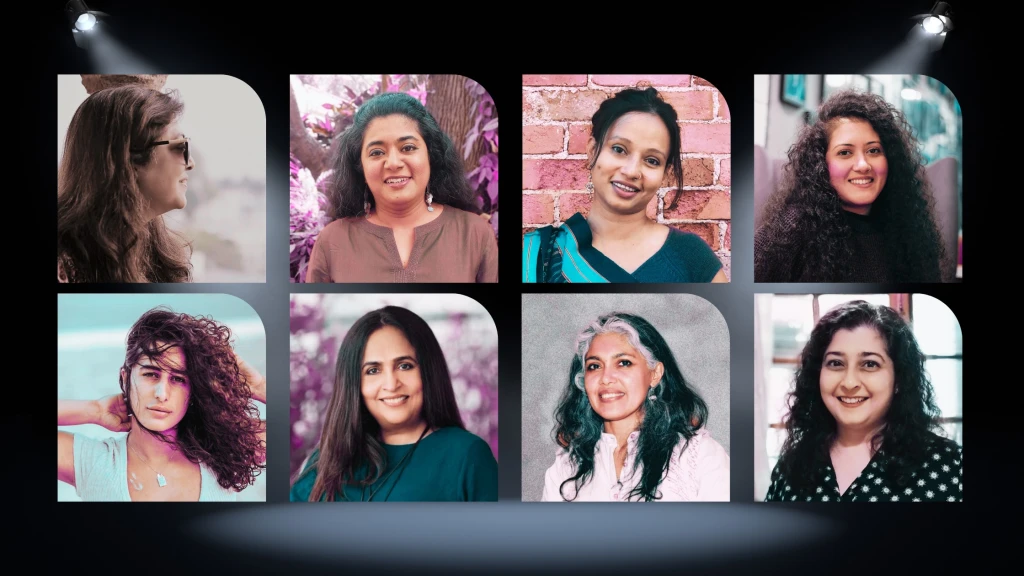

Anchored by Payoshni Mitra – a prominent activist advocating athletes’ rights, and director and trustee of the Geneva-based Centre for Sport and Human Rights – along with Karachi-based sports journalist Natasha Raheel, the panel discussion brought up issues faced by sportswomen across South Asia, from lack of funds to harassment and discrimination. It also brought up heartening success stories of competing on international platforms despite tremendous odds.

Indian speakers included Nisha Millet, who represented India at the 2000 Olympics in Sydney and now runs a swimming academy in Bengaluru, which has coached more than 12,000 swimmers since 2006.

“Post 2004, we have had no improvements in women’s swimming in India. Our boys have qualified eight times for the Olympics. Why the disparity? This is despite the fact that women are leading the way in terms of medal count in other sports,” Millet said.

India won only two medals at the 2016 Olympics, both by women (P.V. Sindhu for badminton and Sakshi Malik for wrestling). Saikhom Mirabai Chanu is the only medal winner so far (as of July 28, 2021) from India at the 2020 Olympics, which end on August 8, 2021.

Other athletes shared grimmer stories from their countries. “War has taken away everything from us,” said Khalida Popal, former captain of the Afghanistan women’s national football team. “It was not easy to play football as a woman in a male-dominated country and in a war zone where women have no voice. But my fight was not only for me, it was for my sisters and for all other women in my country. Football was a movement for us in Afghanistan. From 2007 to 2010, we grew from eight girls to 3,000 women and girls,” she said.

Popal added that she has had to seek asylum in Europe due to the political situation in Afghanistan.

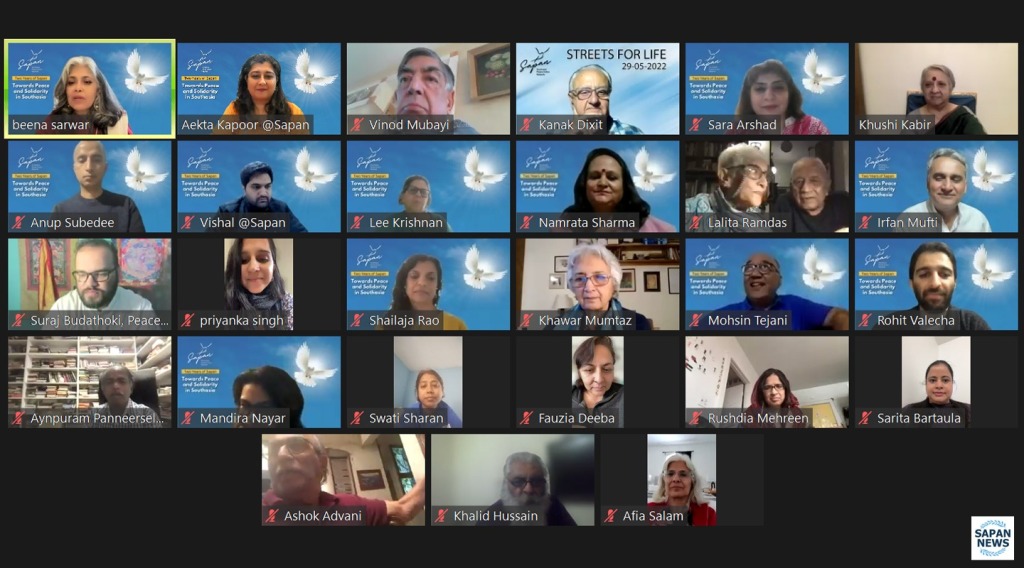

“South Asia is like our home. Our pain is the same. What’s missing is unity,” said Popal during the online discussion, which was hosted by the South Asia Peace Action Network (Sapan), a coalition of individuals and representatives of various organisations working to uphold the values of peace, justice, democracy and human rights in South Asia.

International squash player Noorena Shams, the first ever international female athlete from Malakand Division in Pakistan’s north-western region, also grew up in conflict. “I can still hear the bombs,” she said, adding that she expected to die, and never thought she would play squash, especially at this level. “I disguised myself as a boy to play cricket in Peshawar,” she said. “South Asians should continue to be there for each other. It is not about the trophy or who did it first. We have to do it together and be there for each other,” said Shams.

Several sportswomen brought up the subject of lack of financial help for women athletes. “In Pakistan, women still don’t have the facilities to play sport, and also support their families,” said Sana Mir, former captain of the Pakistan women’s cricket team. She said that – unlike the men’s teams that are given complete financial support to train and develop skills – women’s teams face a severe budget crunch at every level. “Women are set up to fail… we are expected to give the result before funding is given to us. One of the achievements I am proud of is that despite the challenges, in 2014, we had eight girls in the ICC (International Cricket Council) top 20 ranking.”

Funding for women cricketers is also an issue in other South Asian countries. While Rumana Ahmed, captain of Bangladesh women’s national cricket team, rued the lack of sponsorship for women’s cricket, Roopa Nagraj, cricketer and former India-A team player, shared her own struggles with finding a job to support herself and her family. “Other than the Indian Railways, there’s no other public-sector organisation that supports women’s cricket in India,” she said.

Nagraj moved to the UAE seeking a job, and then launched a programme there called ‘Get into Cricket – Girls Only Program’, in which girls above eight years of age are trained for free on Friday mornings. “We now have 150 girls playing cricket and we’ve played two World Cup qualifiers. Women should step forward and take up leadership roles. That’s how we can change things for women’s sport.”

The issue of getting more women into leadership positions was echoed by Ashreen Midha, national basketball player from Bangladesh. She added that women need societal support too. “To get a girl into sports, everyone has a role to play, not just federations and sports bodies. The men in our families too have to speak up for us. Gender inequality is not just a women’s problem to solve,” she said.

Caryll Tozer, activist and former netball player from Sri Lanka, brought up the topic of misogyny and the abusive treatment of women in sport. “There should be no space for racism, colourism, sexism, and homophobia in the sporting world. Sadly, in our region, women are expected to take a backseat to men. Although we have a strong Sri Lankan female cricket team, they are never talked about. We need a systemic change,” Tozer said.

Indian sports investor Ayesha Mansukhani, managing director of telecom infrastructure company Adino Telecom, spoke of the need to change mindsets in mass media and society when it came to women and sport. “Movies and the media objectify women and focus on their beauty. What is the message we are leaving our daughters? Strength, endurance and resilience have their own beauty,” asserted

Mansukhani, who is an avid sportswoman herself and had invested in one of the four women’s football teams in the Adidas Creators Premier League when it was first launched. “Every girl should play sports, whether or not she reaches the professional level. I am here to encourage this, and to help girls in South Asia play,” she said.

There were also encouraging stories of wins despite formidable odds, such as Preety Baral, a national tennis player from Nepal, who said, “When I entered sports, I was the only female player among 30 male players, and there were only two private courts. Now, we have seven government courts and 15 female players. Reaching the international level from a country like Nepal is so overwhelming.”

Mabia Akhter Shimanto, award-winning weightlifting champion from Bangladesh, shared her own journey from being a village girl to reaching the global stage. “Sports was a God-gifted power. Weightlifting gave me recognition,” Shimanto said in Bengali, her words translated for other participants by Sapan volunteers.

Similar stories of overcoming obstacles were shared by Champa Chakma, a cricketer of indigenous origin from Bangladesh, and Gulshan Naaz, award-winning para-athlete from Saharanpur, India, who is visually impaired. “No one wanted to sponsor a blind runner,” she said.

“I am struck by the grit and determination of these sportswomen in very difficult circumstances, and how smilingly they narrated their ordeals,” said analyst Najam Sethi after hearing them speak. Former chairman of the Pakistan Cricket Board, he highlighted two further concerns – the objectification of women and sexual harassment – which deserve more attention.

The event was attended by several noted peace activists including former Chief of the Indian Navy Admiral Ramdas and his activist wife Lalita Ramdas from Alibag, feminist activist Khushi Kabir from Dhaka, and noted educationist Baela Raza Jamil from Lahore.

At a time when women’s clothing has becoming the focus of sports controversies – with the German female gymnastics team at the Tokyo Olympics and the Norwegian women’s beach handball team at Euro 2021 refusing to wear bikini-like garments – the sportswomen of South Asia have the opposite concerns.

A short skit on this subject written by satirist Shoaib Hashmi was performed publicly for the first time at the Sapan event by well-known Pakistani film and television actor Samina Ahmed, supported by Beena Sarwar, US-based founder of Sapan, and Mira Hashmi, Lahore-based author and film scholar. The play had been performed in the 1980s in Pakistan under the repressive military dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq, and had never previously been recorded due to the dangers involved.

In the skit titled Captain Samina, a team of women hockey players is not allowed to play in shorts as the women’s legs are visible, so they decide to wear salwar-kameezes. When that too is not allowed as their faces are still visible, they take to wearing the burqa. When that is also termed inappropriate, since their identities are known, the men’s team plays in place of the women’s team, underneath the burqa. “That way, the girls will also be safe and secure, and the women’s national hockey team will also be strengthened,” Captain Samina says.

In the 40 years since the play was written, the sportswomen of South Asia have finally managed to perform in public, but the playing field is still uneven and the odds still stacked against them. Behind every win, there are innumerable hurdles, handicaps and hardships that come with the game.

Leave a comment